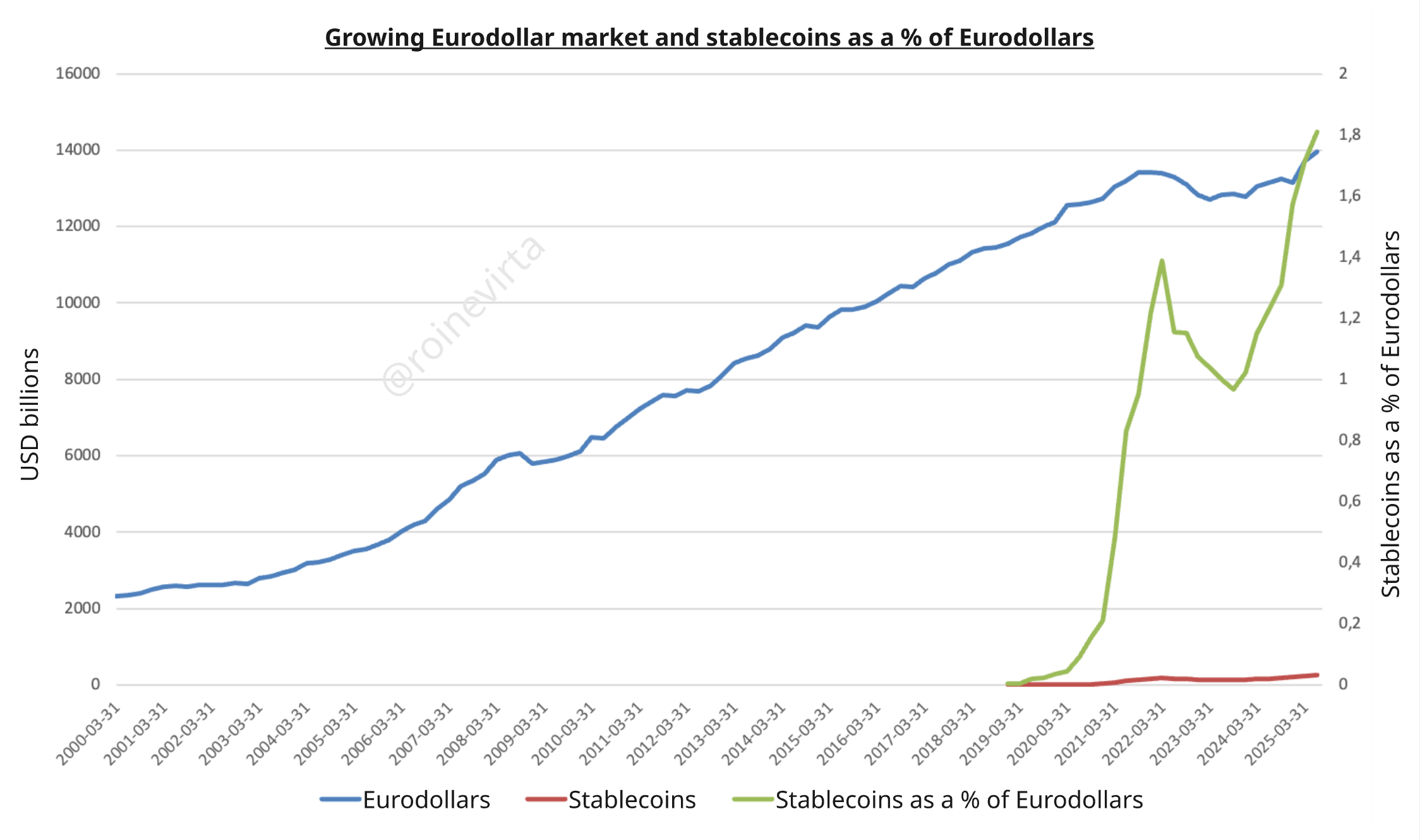

The eurodollar market – dollars held and intermediated outside the United States – has been a cornerstone of the global financial system since its emergence in the 1950s. By June 2010, eurodollar banking amounted “to as much as a quarter or a third of global dollar intermediation”, with 25.1% of global bank balance sheet dollars held outside the US. [S] More recently, the estimated share of US currency held abroad has grown from around 20% prior to 1990 to 50-60% today. [S] Dollar credit to non-banks outside the US, as measured by the BIS, has grown nearly sixfold from $2.3 trillion in March 2000 to $14.0 trillion in June 2024. [S]

Figure 1: Eurodollar market size from 2000 to 2025 (data from BIS, Defillama)

Figure 1: Eurodollar market size from 2000 to 2025 (data from BIS, Defillama)

This offshore dollar market exists because of structural demand for dollars beyond US borders, driven by trade invoicing, commodity pricing, debt servicing, and the dollar’s role as a safe haven. The eurodollar market has performed what the BIS describes as “pure offshore intermediation among non-residents” – it’s not merely an extension of the US banking system, but a parallel financial architecture built on dollar liquidity outside the US regulatory perimeter.

As stablecoins emerge as a superior payment technology to traditional systems – offering interoperability, auditable determinism, programmability, and 24/7 settlement – they should naturally capture an increasing share of dollar intermediation. And if the historical pattern holds, the offshore share should grow faster than the onshore share. This is the thesis behind neoeurodollars: blockchain-enabled dollar stablecoins issued and operated outside the US regulatory perimeter.

Table of Contents

Open Table of Contents

Weaponisation of SWIFT & Geopolitics

US weaponisation of the SWIFT system when Russia attacked Ukraine led sovereigns to reconsider their currency exposures, beyond the financial economic risks. They now have to also consider the political risks. If access to the dollar payment system can be restricted or revoked based on geopolitical considerations, then dollar exposure carries embedded political risk that must be priced.

This realisation creates structural demand for dollar-like instruments that exist outside the direct reach of US enforcement mechanisms. Eurodollars historically served this function in the traditional banking system. Neoeurodollars are will serve this function in the era of blockchain-enabled finance.

Current Stablecoin Landscape

Most stablecoins today, at least when measured by supply, operate within or adjacent to the US regulatory perimeter. Circle, the issuer of USDC, is explicitly regulated in the United States with reserves held and managed by BlackRock. Tether, despite its historically opaque structure, has increasingly positioned itself as collaborative with US law enforcement, with reserves held with Cantor Fitzgerald in the US and public announcements of proactive assistance to the US Department of Justice in criminal investigations and asset seizures.

From a market perspective, this makes sense. The US offers regulatory clarity/flexibility (at least relative to many other jurisdictions) and deep, liquid capital markets for reserve management. But from a neoeurodollar perspective, these stablecoins fail a fundamental test: they have enforceable touchpoints with the US financial apparatus and can be coerced through regulatory, legal, political (Operation Choke Point 2.0, anyone?), or financial pressure.

Neoeurodollars

A neoeurodollar is a dollar-denominated stablecoin issued and operated outside the direct enforcement reach of the US financial system. This definition gives rise to two distinct categories:

Onchain Neoeurodollars

These stablecoins exist entirely on-chain with no interface to the legacy financial system. The canonical example is a collateralised debt position (CDP) stablecoin such as Liquity’s BOLD, which is minted against crypto collateral and exists entirely within the blockchain ecosystem.

Where a fully onchain dollar is properly constructed – meaning there is no vulnerable point in its value or supply chain that could be coerced to change its properties – the stablecoin is, by definition, a neoeurodollar. It exists completely outside the US financial apparatus. No bank accounts can be frozen, no reserve managers can be subpoenaed, no board members can be pressured.

Offchain Neoeurodollars

These stablecoins maintain reserves in the traditional financial system but do so in jurisdictions and through structures that minimise US enforcement touchpoints. This could take several forms, e.g.:

- Fiat-backed stablecoins with reserves held exclusively in non-US financial institutions and jurisdictions

- Strategy-backed stablecoins (functionally tokenised hedge funds) with collateral and operations sufficiently decentralised or non-US domiciled

Offchain neoeurodollars are significantly more challenging to execute on the financial-technical axis. Ethena, the issuer of USDe, reportedly seeks GENIUS approval in the US and maintains USDe positions on US-regulated centralised exchanges, disqualifying it as a true neoeurodollar. Sky’s USDS, despite MakerDAO’s decentralised governance origins, is now predominantly a glorified USDC wrapper, inheriting USDC’s US regulatory touchpoints.

¿Tether?

Tether occupies an ambiguous position in this framework. Historically, Tether has served as the de facto neoeurodollar – a dollar stablecoin that, despite regulatory uncertainties, operated largely outside the US regulatory perimeter. Its growth relative to alternatives, particularly in markets where US regulatory reach is limited or unwelcome, suggests the market may view it as fulfilling this role.

However, Tether’s recent public positioning – emphasising collaboration with US law enforcement and reserves held with Cantor Fitzgerald – suggests a strategic shift toward integration with, rather than independence from, the US financial system. Whether Tether can maintain its neoeurodollar perception while building these US regulatory relationships remains unclear.

Onchain vs Offchain & Scalability

Historically, onchain dollars have underperformed their offchain counterparts in supply growth, primarily due to scalability constraints and liquidity (w.r.t. traditional banking system) challenges.

Offchain stablecoins scale with demand. If someone wants to mint $1 billion in USDC, they deposit $1 billion with Circle and receive tokens. The constraint is the size of the addressable market for dollars, not the supply of on-chain collateral.

This scalability asymmetry explains why USDC and USDT dominate. But it also highlights the challenge for neoeurodollars: the largest and most liquid neoeurodollar candidates (offchain versions) require non-US banking infrastructure at significant scale, while the most credibly non-US versions (onchain) face fundamental limits.

Why Haven’t Neoeurodollars Emerged?

Several factors explain the current gap:

-

Regulatory uncertainty: Issuers prefer jurisdictions with clear frameworks (recently, only MiCA would’ve been such but the cost of issuance is too high in the EU).

-

Tether’s ambiguous position: Demand for explicit alternatives is muted by the extent to which Tether is viewed as a neoeurodollar.

-

Infrastructure gaps: Large-scale offchain neoeurodollars require deep, liquid, dollar-denominated banking relationships outside the US. Few jurisdictions offer this at scale with sufficient regulatory clarity (perversely, where these deep markets exist, crypto isn’t too welcome).

The Case for Neoeurodollar Growth

Neoeurodollar growth should (continue to(?)) be driven by the following factors in the coming decade:

Secular Geopolitical Tailwinds

The 2022 SWIFT weaponisation demonstrated that access to dollar payment systems carries political risk. This creates structural demand for dollar instruments outside US control. As more institutions and sovereigns internalise this risk, demand for credible neoeurodollars will grow.

Superior Technology

Stablecoins are simply better payment technology than correspondent banking, ACH, SWIFT, or FedNow. They offer 24/7 settlement, programmability, atomic transactions, and transparent auditability. As this technology advantage becomes more apparent, adoption will accelerate and offshore adoption may accelerate faster than onshore adoption due to weaker incumbent payment infrastructure.

Historical Precedent

The eurodollar market has consistently grown as a share of total dollar intermediation. In 1960, eurodollars were negligible; by 2010, they represented 25-33% of global dollar intermediation. There’s no reason to expect this secular trend to reverse in the blockchain era. If anything, blockchain technology should accelerate it by reducing the costs and frictions of offshore dollar intermediation.

(Growing USD Dominance Thesis)

An additional tailwind, which I doubt a bit more than believe in, is that the USD maintains or grows its relative global economic position. Therefore, with stablecoins as the superior payment technology, total USD stablecoin supply should grow. And if the historical pattern holds – that the market for dollars outside the US grows faster than within the US – then neoeurodollar supply should grow faster than domestic neodollar supply.

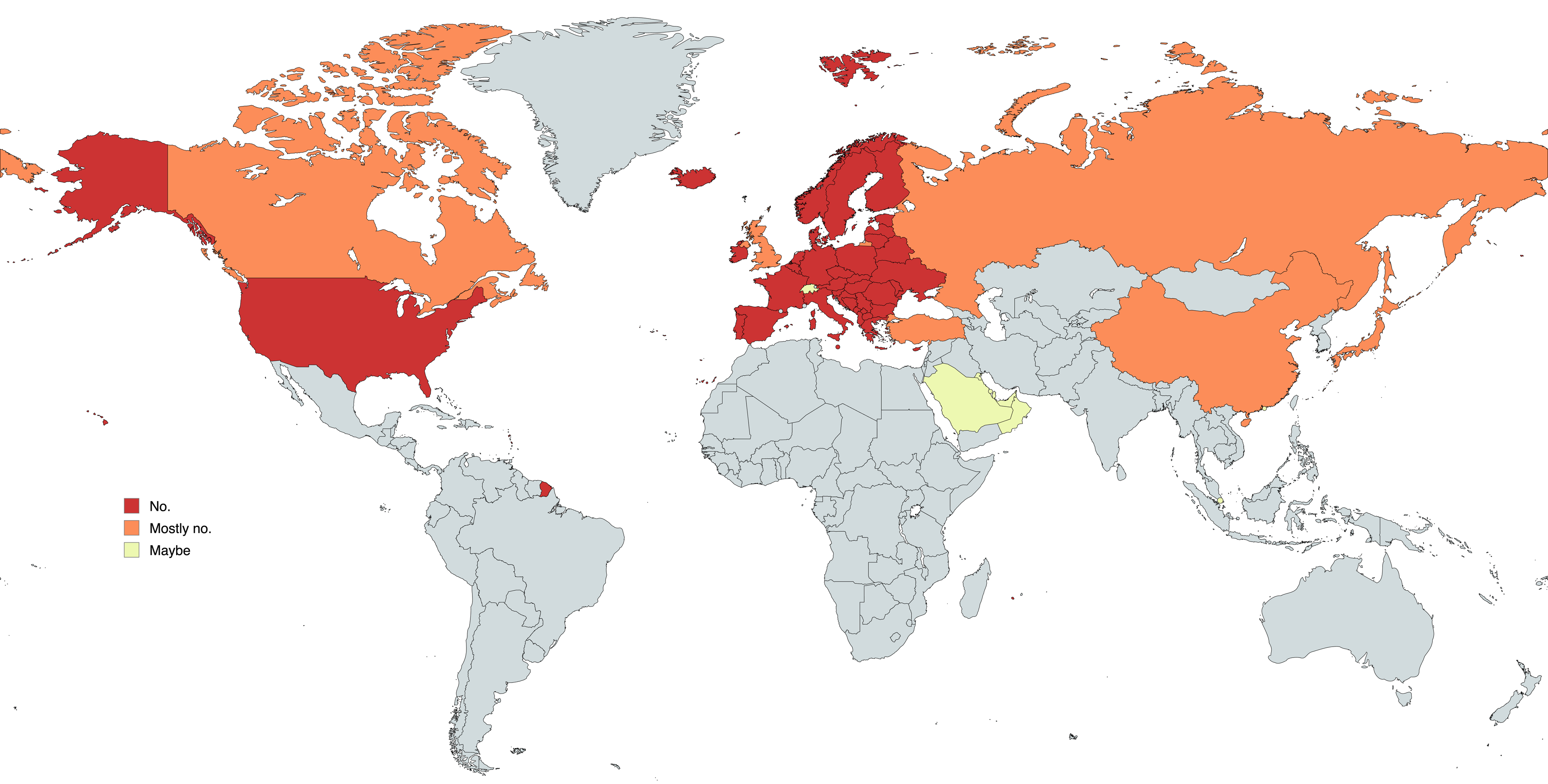

The Jurisdictional Question

The biggest open question is not whether neoeurodollars will grow, but where they will be based.

The most successful neoeurodollars will likely be offchain-collateralised due to their superior scalability and liquidity characteristics. But offchain stablecoins require a physical location and jurisdiction. They need banking relationships, custody solutions, legal structures, and regulatory frameworks.

The ideal jurisdiction would offer:

- Existing deep, liquid dollar-denominated banking relationships

- Clear stablecoin regulatory framework

- Credible independence from US financial coercion

- Strong rule of law and property rights

- Access to crypto-native talent and infrastructure

Candidates might include Switzerland (excellent historical track record), Singapore, Hong Kong (though its relationship with China complicates independence from geopolitical pressure), potentially GCC countries, or other emerging offshore financial centres positioning themselves for the crypto era. The EU, despite MiCA’s clarity for stablecoins, is not feasible due to the cost structure it imposes. Regulatory hurdles also surround the historical eurodollar market capital, London, as the UK FCA’s stance on crypto is still yet to thaw.

Figure 2: Where neoeurodollars might (not) be based in

Figure 2: Where neoeurodollars might (not) be based in

Conclusion

The eurodollar market has grown from near-zero in 1960 to a global dollar behemoth. This growth reflects structural demand for dollars outside the US regulatory perimeter and the efficiency gains from offshore intermediation.

Neoeurodollars – blockchain-enabled dollar stablecoins issued outside US regulatory reach – should follow the same trajectory. They benefit from both secular geopolitical tailwinds (politicisation of the traditional dollar payment system creating demand for alternatives) and technology-driven growth (stablecoins as superior payment infrastructure).

The current landscape is immature. Most dollar stablecoins operate within the US regulatory perimeter. Tether’s role as a de facto neoeurodollar is ambiguous and possibly transitioning. True neoeurodollar alternatives barely exist.

The combination of structural demand, technology superiority, and historical precedent makes neoeurodollars inevitable. Their growth will be exponentially exponential. The remaining question is in which jurisdiction they will emerge and which issuers will execute first/best.